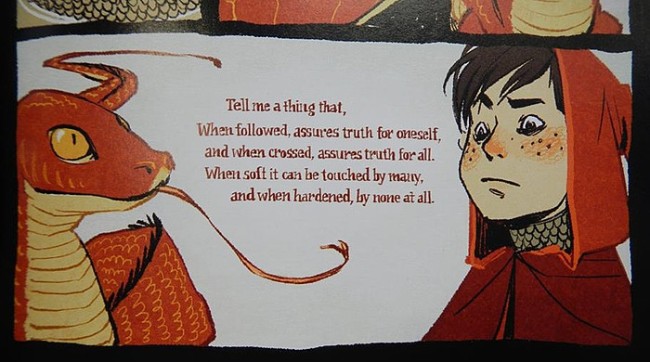

Panel in “Riddle” by Kyla Vanderklugt p. 49 of Flight Vol. 8

New life-challenge for me: turn curiosity into courageous questions quickly.

Not so new but still challenging for me to do: elicit passion and wisdom from other people as soon as appropriate.

“Art ain’t about paint. It ain’t about canvas. It’s about ideas. Too many people died without ever getting their mind out to the world.” — Thornton Dial, SR.

Art, as I’ve come to understand, exists as a special form of communication. It’s communication that inspires a sense of wonder—a deep curiosity that has us ponder the encounter and ideas behind what we engage. It compels us to activate our curiosity as we wonder about the possible implications an encounter can have on our lives or the that of others.

I saw Thornton Dial SR.’s quote in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s folk artist exhibit. It was liberating as much as it was validating: To make art, one requires no rigorous history of training, art degree, special materials or extraordinary circumstances to start. To me, Thornton Dial’s quote was an invitation to make whatever was on my mind if I so wished to do so. Better yet, it comforted me to know there’s boundless opportunity to share any idea, including those that can’t be experienced in writing. Perhaps what we have to share comes forth as good and beautiful. Whatever we choose to do, the act of honestly communicating our ideas certainly brings us closer to truth for our minds and hearts. Whenever that happens, it’s an invitation to live life artfully.

Looking at Mr. Dial’s quote again, it also applies to how I look at living life when speaking with and listening to people. There’s an art to good conversation and dialogue. If we consider Seth Godin’s distinction between the characteristics of work and art, artful conversation becomes a palpable ideal. Godin believes that work can be recognized as something people want to do less of, while art is something people want to make more. In that sense, we can all strive to make artful conversations. Both are important, good work can be necessary for creating better art.

I believe everyone benefits being in and moving from a place of passionate curiosity. Being as Rachel Carson describes, in a “sense of wonder”. When activated, it entices profound intrigue straight from the spirit. Whether mentally or physically, that place could be our own, among others, or perhaps better yet: shared. What matters most is that we speak with the flames of inspiration, those burning deeply from within our being to create that place.

If there’s dead space or if confusion nags at your attention in a way that prevents peace for everyone in the conversation, call it out and help shake things up. Time and life in the presence of another person are too precious an opportunity to squander. For anyone who grants me the privilege of sharing a conversation, this applies to us too. Call me out if I don’t do so first. Just because I’m familiar with the recesses of awkward pause doesn’t mean I necessarily need or want us to stay there.

Perhaps the cost of very good conversation comes from committing yourself wholly to the people you speak with by thoroughly listening and keeping the courage to share what really matters to you. But do so in the greater interest of co-creating an enriching dialogue for everyone involved. Live boldly. Don’t be cautious, but be considerate with presence, intelligence, and equal heart. With this in mind, we can strive to create heartful conversations.

I’m still learning how to do so with excellence. But I like the idea that it’s an endeavor to live and share.